More than 100 million people around the world are migrant workers seeking better opportunities in a foreign country, says the International Labour Organisation. Last year more than half a trillion dollars was sent home by migrant workers, and the amount sent to developing countries has more than quadrupled in the past decade.

Among the biggest destinations for migrant workers is the Gulf region, whose fast-growing, resource-rich countries have attracted millions of labourers from South Asia, East Asia - and, increasingly, Africa.

Workers in the six countries that make up the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) sent home about $61bn in 2011, the last year for which full data is available. Labourers in Saudi Arabia remit more money than those in any other country except the United States. In 2011, Gulf workers sent home almost as much money as foreign workers in Europe's three biggest economies combined: Germany, France and the UK.

India is the biggest beneficiary, receiving about $30bn in remittances from the Gulf states in 2012. "Remittance flows from the [Gulf states] provide a lifeline" to developing countries, said Dilip Ratha, the manager of the World Bank's Migration and Remittances Unit.

Although the Gulf's economic growth has provided millions of jobs to people from developing countries, states in the region and in the Middle East more broadly have been criticised for failing to protect labourers from poor working conditions and abuse. In April 2013, the United Nations' International Labour Organisation reported that an estimated 600,000 migrant workers are "tricked and trapped into forced labour across the Middle East".

Rights groups are also strongly critical of the kafala system, used across the Gulf, which binds workers to a single employer and limits workers' ability to change jobs. This system facilitates forced labour, they say, adding that domestic workers - who are not covered under Gulf countries' labour laws - are particularly vulnerable.

Remittances and population

Select a country to view estimated amount of remittances sent in 2011.

* Data on remittances between countries are estimates made by the World Bank

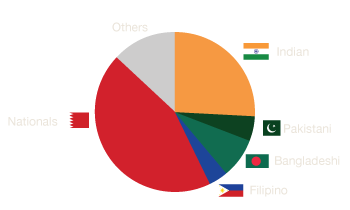

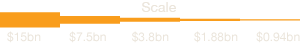

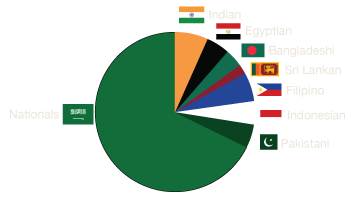

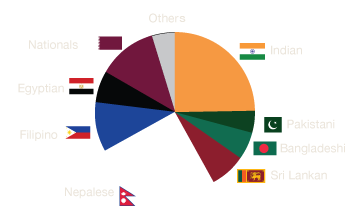

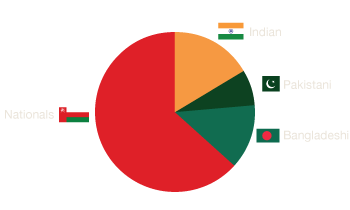

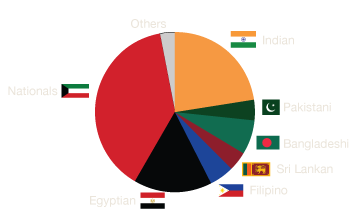

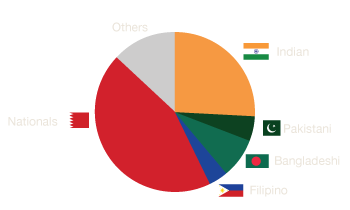

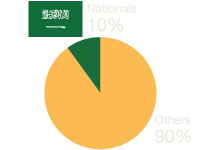

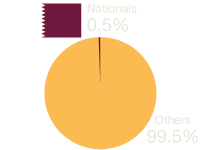

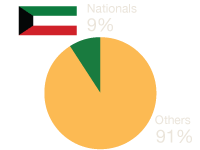

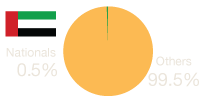

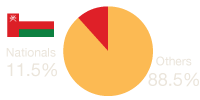

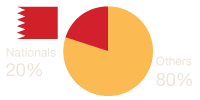

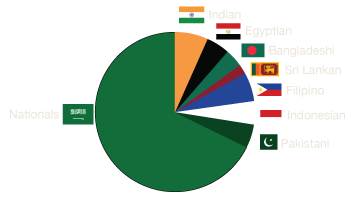

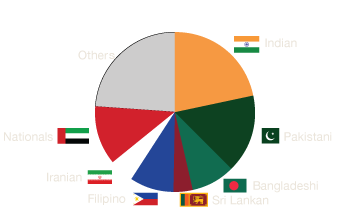

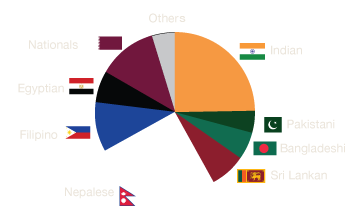

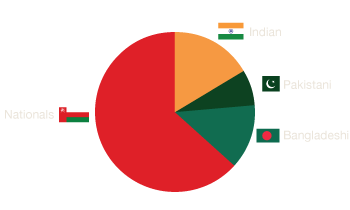

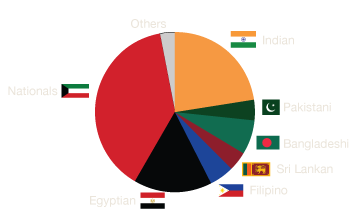

Because there is little official data publicly available on the number of foreign workers by nationality living in each Gulf country, these charts should be treated as very rough estimates. The pie charts below rely on data obtained from conversations with embassy officials and previously published news articles. Census data was used to obtain the number of each Gulf states' citizens. Nationalities comprising less than 5 percent of a given Gulf country's population are not shown. Because of the imprecise data and 5-percent cutoff, some pie charts will appear to show that there are no workers of the nationalities not listed, though this is not the case.

Why are there no percentages above ? ▼ EXPAND ▼

| Top five receivers: |

| India |

$7.62bn |

| Egypt |

$3.15bn |

| Philippines |

$2.65bn |

| Pakistan |

$2.59bn |

| Bangladesh |

$1.32bn |

| Source: World Bank |

Saudi Arabia

Population (2011): 28 m

Why are there no percentages above ? ▼ EXPAND ▼

| Top five receivers: |

| India |

$14.25bn |

| Pakistan |

$1.49bn |

| Philippines |

$0.70bn |

| Egypt |

$0.65bn |

| Sri Lanka |

$0.50bn |

| Source: World Bank |

UAE

Population (2011): 7.9 m

Why are there no percentages above ? ▼ EXPAND ▼

| Top five receivers: |

| India |

$2.08bn |

| Nepal |

$1.69bn |

| Pakistan |

$1.08bn |

| Philippines |

$0.91bn |

| Egypt |

$0.48bn |

| Source: World Bank |

Qatar

Population (2011): 1.9 m

Why are there no percentages above ? ▼ EXPAND ▼

| Top five receivers: |

| India |

$2.37bn |

| Bangladesh |

$0.45bn |

| Pakistan |

$0.24bn |

| Egypt |

$0.16bn |

| Sri Lanka |

$0.10bn |

| Source: World Bank |

Oman

Population (2011): 2.8 m

Why are there no percentages above ? ▼ EXPAND ▼

| Top five receivers: |

| India |

$2.67bn |

| Egypt |

$1.52bn |

| Bangladesh |

$0.87bn |

| Sri Lanka |

$0.67bn |

| Philippines |

$0.51bn |

| Source: World Bank |

Kuwait

Population (2011): 2.8 m

Why are there no percentages above ? ▼ EXPAND ▼

| Top five receivers: |

| India |

$0.69bn |

| Pakistan |

$0.14bn |

| Egypt |

$0.13bn |

| Philippines |

$0.13bn |

| Iran |

$0.03bn |

| Source: World Bank |

Bahrain

Population (2011): 1.3 m